PART I: Lewis S. Fisher, AIA Emeritus

For many years, San Antonio has been known for its casual blending of cultures. Writers in the 19th century often mentioned the mixture of languages and skin colors when describing the people of San Antonio, an unexpectedly quirky place on the western frontier. But the city did not always have a blended character.

San Antonio was founded by a marriage of the Spanish government, in the form of soldiers of the Viceroyalty and their multi-racial families, with the Franciscan Order of the Roman Catholic Church, which brought a few mixed-culture families from Mission Solano on the Rio Bravo. This was not a match made in heaven. In fact, the two groups were not in agreement from the start and made separate journeys across the wilds of Southwest Texas to the San Antonio River valley in 1718. Upon arriving they encamped on different sides of the San Pedro Creek. A year later they both moved to new sites, this time on different sides of the San Antonio River, and further apart.

In 1731 a third culture arrived on the scene, Spanish citizens from the Canary Islands who expected to continue the traditions and lifeways they had known in their homeland. New Spain lived by a strong and well-defined caste system based on the primacy of European Spanish ancestry and the various forms of intermarriage with Native Americans and African Americans. The Islanders, or los Islenos, considered themselves true Spanish, and had been given the title of hidalgo as part of their enticement to go to San Antonio. Hidalgo is the lowest level of aristocracy, a son of somebody (hijo de algo), but a person of importance nonetheless. The Islanders were provided with a site adjacent to the army’s presidio where they laid out their villa according to the Law of the Indies, the Spanish guide defining how towns must be established in the Americas. The first site to be determined was that of the parish church from which the plaza and home sites would radiate.

The remainder of the 18th century was a dance between these different groups that were brought together to find a way to survive in a beautiful but inhospitable environment. Records describe the disagreements between members of the groups. There was no parish church for the Islenos until the 1750s, and they didn’t like attending mass in the inadequate chapel of the presidio alongside the soldiers. And when the Spanish women waded across the river to attend mass in the chapel of the Mission San Antonio de Valero, the Franciscan priest complained they were a bother to his Native American flock. The town council went so far as to outlaw the settlement of the potrero, the pasture that was within the horseshoe bend of the river. This was to assure that the citizens of the Villa did not get entangled with the Native Americans at the mission.

But the laws of nature and humanity often outflank the laws of nations and God. Eventually there were marriages between the groups, and offspring to soften a grandfather’s heart. A laborer, who was from a lower class, might be sporting the title of “Don” by the time he was an old man.

In the early 19th century, the Spanish army planned for a new barracks facility to house the increase in troops needed to protect San Antonio from the expanding hordes of Americans streaming west towards its state of Coahuila y Tejas. The site chosen by the Spanish was land that they held south of the river bend. The barracks were built of wood, probably meaning of “palisado” construction. Palisado construction relies on posts, probably of local juniper trees, set vertically in the ground, one post adjacent to the next, to form a wall. A mud plaster is installed with wooden lath to cover the posts. A roof of wood framing with thatching would have completed the structures.

< Wall built with palisado construction

Soldiers were paid by the crown and had cash to spend. Soon citizens were petitioning for grants for land near the new barracks. Lots were granted, and new public streets were defined. Thus, la Villita came into being, a settlement area separate from the villa, the presidio, and the mission.

An early recipient of a land grant was Don Antonio Martinez, who in 1797, received land on the south bank of the riverbend to create a corral for his cows. Later, a house was built on the property facing a section of the Camino Real, later known as Villita Street. It was in this house that General Martin Perfecto de Cos signed the articles capitulating to the Texians after the Siege of Bexar, December 1835. The victory was short lived. When General Santa Anna arrived two months later, he established an artillery post on the edge of La Villita, from which the Alamo fortress was shelled.

Martinez - Cos House prior to restoration, ca. 1935

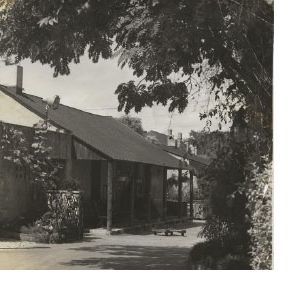

A devastating flood in 1819 caused another rush by citizens of the villa to petition for land grants in La Villita on the high bank of the river. The houses being built were often of palisado or adobe construction with gabled and thatched roofs. The Tejeda and Herrera houses are examples of homes built in this time. The “little village” grew but became dilapidated and damaged by the turmoil of the Mexican and Texas revolutionary periods.

< Herrera House, Ca. 1954 (after restoration). Photograph in the collection of Lewis S. Fisher

< Herrera House, Ca. 1954 (after restoration). Photograph in the collection of Lewis S. Fisher

Lewis S. Fisher, AIA, of San Antonio, is a retired architect and scholar director of the Texas Historical Foundation.

Author’s Note: Thanks are extended to Maria Watson Pfeiffer for the use of her historical research, which was provided to Fisher Heck, Inc. Architects to develop a series of interpretive markers for the buildings of La Villita. This project was sponsored by the City of San Antonio in its ongoing commitment to preserve La Villita. Stay tuned next month for the second part of Lewis S. Fisher’s blog, which takes readers on a tour of La Villita from the 1850s to present day.

Stay tuned next month for the second part of Lewis S. Fisher’s blog, which takes readers on a tour of La Villita from the 1850s to present day.