Hugh Edmondson’s family are ranchers in Ballinger, outside of San Angelo. In the 1860s, the Goodnight-Loving Trail, named for cattlemen Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving, was used to move herds from Texas to western markets, and it went across land the Edmondsons would eventually own.

When his father found a single old spur on their ranch 60 years ago and then showed it to his son, Edmondson held the object in his hand and wondered about the cowboy who had worn it. He suspected the spur dated back to those cattle drives. Further research confirmed his intuition and revealed the name of the maker: August Buermann, a German immigrant and Civil War veteran.

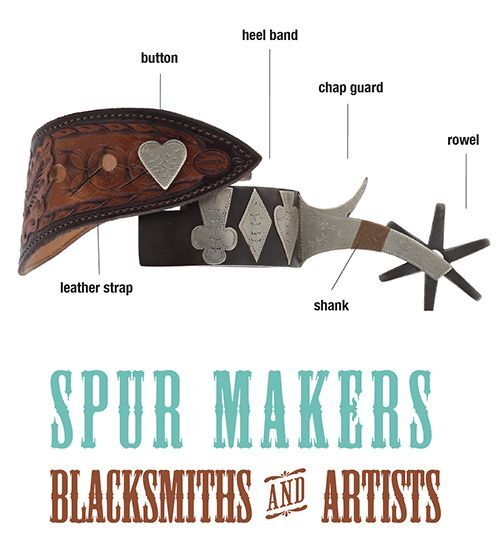

This simple discovery began a journey by Edmondson that would eventually lead him to assemble what is now a collection of spurs that includes examples covering a span of 120 years. Edmondson used the book Bit & Spur Makers in the Texas Tradition: A Historical Perspective by Kurt House to guide him in assembling his collection. “I wanted to find at least one pair from all the old Texas spur makers, and I came close. I got 60 out of the 65, and I’ve still got my eyes open for the ones I’m missing.”

Recently, Edmondson donated more than 125 historic and contemporary spurs to the W. K. Gordon Museum at Tarleton State University, and he continues to add to that number. The Stephenville college is the alma mater of both Edmondson and his wife. Some of those spurs—and stories about their makers—were highlighted in an article that appeared in the Texas Historical Foundation award-winning Texas HERITAGE magazine.

Edmondson shared even more collecting details during an unplanned, but thoroughly delightful, recent phone call.

• For owners of spurs who might be thinking of splitting up the pair—perhaps to share among family members or heirs—Edmondson advises against that. “That’s really the worse thing a person could do value-wise.” To a collector, he said, a single spur is worth about 1/10 of the total worth of a pair of spurs.

• While talking about the makers whose work is represented in his collection, Edmondson spoke about J. C. Petmecky. A Civil War veteran, he did not often mark his spurs, which makes them difficult to recognize. Edmondson said that Petmecky inlaid brass and used rivets that were mounted in silver and gold on his spurs, leading them to land in the hands of high-end clients who could afford those expensive details.

• Other makers came up in the conversation, including many highlighted in Kurt House’s book. Edmondson said that only two Hispanics are profiled there, including Lucio Manriquez, who is credited with the creation of the Marfa Shank style, a combination of two spur designs that was popularized by cowboys of the Texas Big Bend. Manriquez worked as a mechanic and blacksmith, including 12 years in that capacity for the Presidio Mining Company in Shafter, which ran the longest operating silver mine in the state from 1883 until 1942. Edmondson said that only two African American spur makers are in the book, including Louis Marvin “Cowboy” Traylor, who learned the trade while serving prison time in Clemens Unit in Brazoria during the 1920s.

• While some Texas spur makers, such as J. R. McChesney are acclaimed, there are also great artists who toil in relative obscurity. In that vein, Edmundson mentioned little-known Jesus Morales, from Cotulla, in South Texas, who was killed in a car-pedestrian accident in the 1960s. “He was extremely creative and did amazing things with very few tools. Morales didn’t even own a hammer; he used the head of a pipe wrench to make his spurs, and they were spectacular.”

Spectacular is also a word that could be used to describe Edmondson’s depth of knowledge. There are collectors who simply want to own artifacts, and there are others who seek to know about the history of the items they have assembled. Edmondson falls into the latter category. He laughingly called his collecting habit, “a disease.” But other words come to mind for me—such as intellectual curiosity and extreme generosity—given Edmondson’s willingness to openly share what he has learned and then donate pieces of his collection to a public university—and by extension the people of Texas.