By Bernie Sargent

Texas Historical Foundation

Director - El Paso

In a small mining settlement 235 miles southwest of Chihuahua, Mexico, New Englander John Robinson, a former business partner of William Fargo, of Wells Fargo fame, purchased a silver mine and changed the name to Hacienda Robinson. During Robinson’s ownership, many improvements were made to increase the efficiency and hence the profits. The Serna family worked the mines, and their story is the topic of this research.

The success of the mining operation drew the attention of the leadership of Mexico, leading to more and more bureaucratic control. The French invasion of the country, followed by the Porfirio Diaz revolt, and the death of Robinson’s sons and grandchildren from typhoid, gave cause for the owner to sell his interest in the mines and return to the United States.

In 1876, the former Governor of the District of Columbia Alexander Shepherd purchased the property and immediately began modernizing the operation to include upgrading the utilities, roads, and rail system of the nearby community of Batopilas, helping improve the lives of the people and increase the profitability of the mines. But as history has demonstrated, politics as well as the falling silver prices spelled disaster for the community and the investors in Hacienda Robinson.

By 1896, trouble was brewing in the community causing a rapid decrease in employment levels. The Serna family was impacted as were many others in the area. Alexander Shepherd died suddenly, leaving the operation to his son who passed away one year later. Unrest grew in the community, and by 1910 most Americans left, concerned for their safety.

When the Mexican Revolution began, it was apparent to most that young people would either be conscripted by the military or the revolutionaries. These choices weren’t palatable to a member of the Serna family, Marcelino, who in 1916 traveled north to America in search of a future. He crossed the border into El Paso where, even though he spoke no English, found work on a railroad maintenance crew. The young man then traveled to Colorado, where he performed seasonal work in a beet field. It was there that he was taken to Fort Morgan, Colorado, by military police searching for draft dodgers. When they learned that Marcelino wasn’t an American citizen and could not speak English, he was offered the opportunity to return to Mexico. Instead, he opted to join the U. S. Army and was immediately sent to Camp Funston, Kansas, for three weeks of basic training. He, along with fellow members of the 89th Division 355th Infantry, where then deployed on May 21, 1918, to Camp Mills, Long Island. Shortly thereafter, the regiment boarded the transport RMS Adriatic in Hoboken, New Jersey, and set sail for England, arriving in Liverpool on June 16. After a brief stay at Camp Woodley, they marched to Southampton and boarded a small steamer for La Havre, France.

The soldiers conducted final training activities before boarding motor buses, a new means of transportation for the U. S. Army, and moved to the front near Beaumont on August 4. Shortly thereafter, the 1st battalion of the regiment became the first unit from the division to occupy the active front, and it was subjected to an intense gas shell bombardment. The unit continued to the front lines conducting raids, patrolling the enemy wire, capturing prisoners, and gathering information for the upcoming offensives. It was during these engagements that Serna fought in the Lucey Sector, the Saint-Mihiel offensives, the Euvezin Sector, and the Meuse-Argonne offensive. On September 12, 1918, during the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, Private Serna’s unit came under heavy machine gun fire, resulting in the deaths of 12 soldiers. Following that event, Serna volunteered to scout ahead. The young soldier advanced alone until he was close enough to the machine gun emplacement to toss four grenades inside. The blast killed six, and Serna captured the remaining eight German soldiers. Two weeks later, during the Meuse-Argonne offensive, he again volunteered to scout ahead alone after spotting a sniper in the distance. Following the shooter to a German trench and armed with an Enfield rifle, pistol, and grenades, Serna laid down fire while continually changing positions around the trench. The enemy came to believe that they were under attack by a much larger force and surrendered. Serna single-handedly killed 26 enemy soldiers and imprisoned 24 others. When reinforcements arrived, Serna defended those captured from American soldiers, who wished to shoot them on the spot, and argued that such executions went against the rules of war. On November 7, 1918, Serna was hit by sniper fire in both legs and sent to a military hospital in France, where he spent Armistice Day, November 11, 1918.

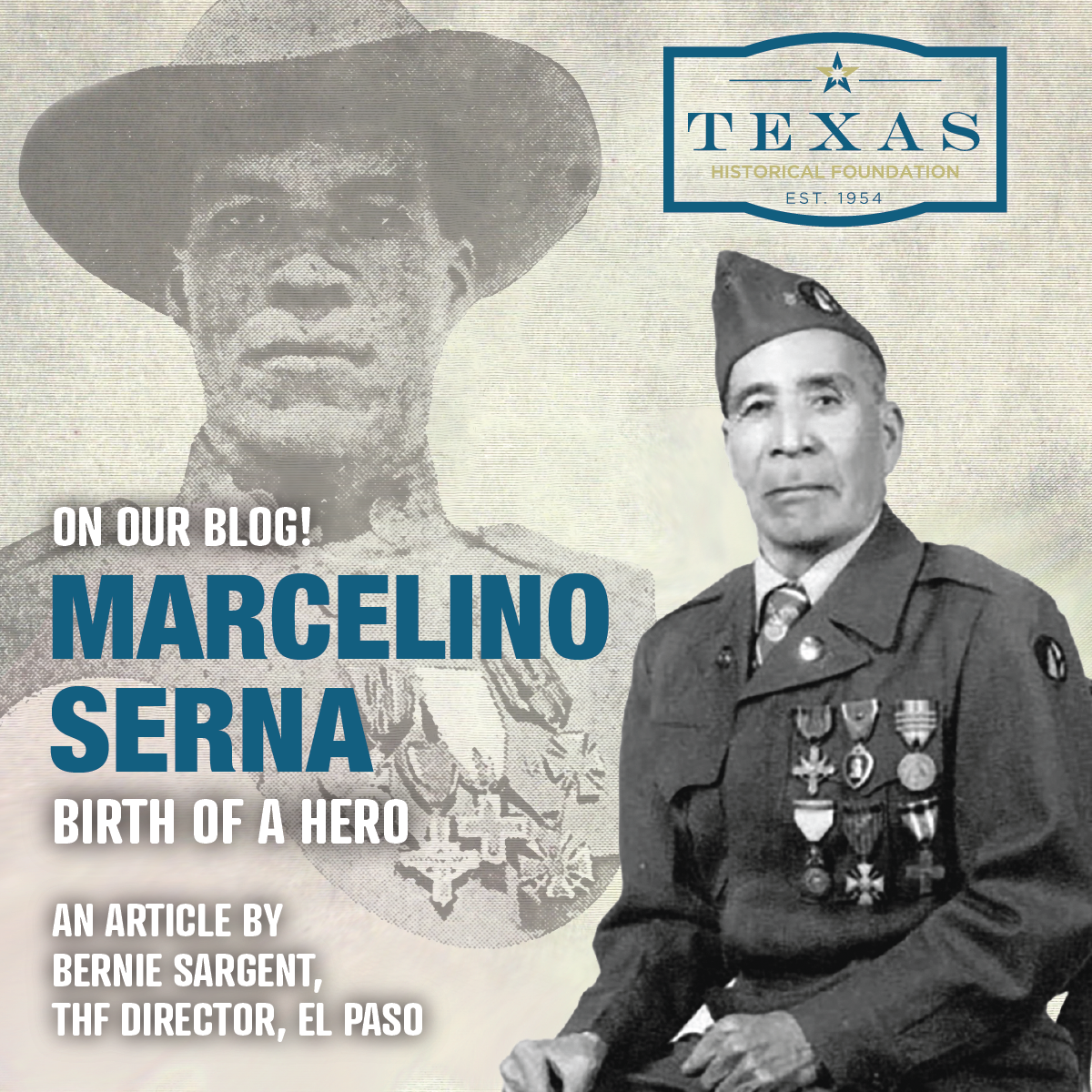

For his service, Serna was awarded the second-highest American combat medal, the Distinguished Service Cross, by the commander-in-chief of the American Expeditionary Forces General John J. Pershing. He also received two French Croix de Guerre with palms. The first was given to him personally by French Marshal Ferdinand Foch, supreme commander of the Allied forces in Europe. The second, along with a French Médaille Militaire and an Italian Croce al Merito di Guerra, was awarded in a ceremony at Fort Bliss attended by Governor William P. Hobby. In addition, the young soldier received, a French Commemorative Medal, a French St. Mihiel Medal, a Victory Medal with five stars, a Victory Medal with three campaign bars, and two Purple Hearts, making him one of the most highly decorated soldiers in Texas history.

Serna was discharged from the U. S. Army in May 1919 and returned to El Paso. His intention was to lead a humble life in his newly adopted home. He lived so simply and anonymously, in fact, that the government had a difficult time locating him to present several more well-deserved medals. Once he was found, Governor W. P. Hobby, Major General Howze, and Brigadier General Erwin gave Serna the French Croix de Guerre with Palm, along with a French Médaille Militaire and an Italian Croce al Merito di Guerra, at a formal ceremony at Fort Bliss on September 11, 1919.

As a civilian, the war hero worked briefly at the Payton Packing Company before landing a job in the quartermaster’s department at Fort Bliss. In 1922, he married Simona Jiménez, and two years later, became a U. S. citizen. Later, he worked as a city truck driver, a civil service employee at Fort Bliss, and a plumber at William Beaumont Army Medical Center, where he retired in 1961. Ever loyal to his new country, Serna even attempted to re-enlist in the Army during World War II but was turned down due to his age.

Serna and his wife had six children, but only two survived to adulthood. He became a charter member of Veterans of Foreign Wars Post No. 2753 and remained active in the organization for many years, often appearing in Veteran’s Day parades. A devout parishioner of Saint Ignatius Catholic Church, Serna died in El Paso on February 29, 1992, and was buried at Fort Bliss National Cemetery with full military honors.

In May of 2016, U.S. Congressman Will Hurd introduced H.R. 5252 to designate the United States Customs and Border Protection Port of Entry located at 1400 Lower Island Road in Tornillo, Texas, as the "Marcelino Serna Port of Entry." On April 20, 2017, the official naming of the Tornillo Port of Entry in honor of Marcelino Serna took place.

Sources:

“Marcelino Serna Became a World War I Hero.” El Paso Community College. 2004.

“U.S. Latino Patriots.” “Marcelino Serna, American Hero” El Paso Times. May 29, 2016, “El Paso Herald Post”, “Honolulu Star-Bulletin”, “The War Society of the 89th Division”, “El Paso Inc.”,

“The Alexandria Times-Tribune”, (Alexandria, Indiana), “The Star Press” (Muncie, Indiana),