North American colonial ranchers first observed the effects of southern cattle fever, a tick-borne disease, as early as the mid-eighteenth century. Symptoms included “high fever, swollen spleen, engorged liver, thick bile, and bloody urine.”[1] Although the disease originated outside of Texas, it became increasingly prevalent among Texas longhorns. Carrier herds exhibited few, if any, outward signs of the fever due to their acquired immunity. When ranchers drove them north through the Panhandle and into the Midwest, however, they infected previously unexposed cattle that could not suppress the disease.[2] Even allowing herds to graze in the same pastures from which infected longhorns had moved on caused them to fall ill, resulting in the deaths of thousands of cattle.

Local and federal entities responded to the surge in southern cattle fever. Ranchers outside of Texas imposed strict quarantines on the state’s herds to protect their financial investments in their own cattle. President Chester A. Arthur signed the 1884 Animal Industry Act in response to spreading animal-borne diseases like southern cattle fever and to prevent infected animals from being used as food. The act created the Bureau of Animal Industry under the U.S. Department of Agriculture.[3] Working for the bureau in the summer and fall of 1885, Colonel S.P. Cunningham conducted a study across Texas and other affected states in which he documented several possible quarantine lines to check the southern fever’s spread.[4]

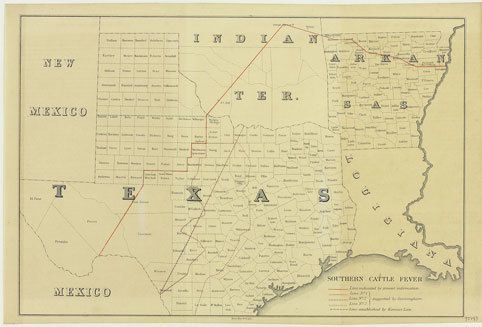

This map appeared alongside Cunningham's final report in 1885, the same year Kansas banned all importation of Texas cattle. The green dashed line in the Panhandle depicts the boundary that cattle drives from the U. S. South and Southeast, where most drives originated, were no longer permitted to cross. The law cut off the valuable Kansas grazing land along the often-used Western and Chisholm trails, forcing Texas cattlemen to reroute their herds.[5] A solid red line beginning in the southwestern corner of Pecos County continues northeast through Texas and into Indian Territory before proceeding southeast through Arkansas. It marks the initial – and most restrictive – quarantine recommendation based on researchers’ knowledge of infection patterns.

Cattle north of the quarantine line were considered healthy, and those south of the line were thought to be potentially – but not universally – unsafe. The “safe” zone accounted for only approximately 22 percent of all Texas cattle. Cunningham collaborated with established cattle drivers and the Committee of Brazos and Colorado Cattlemen to refine their understanding of infection data and establish geographical areas thought to be occupied by healthy herds. He noted, however, that more thorough data collection would provide better insight. He wished “to be clearly understood” that it was “impossible to absolutely define a line above which all cattle are free from imparting the disease and below which all give off the fever.”[6]

The map includes three additional proposed quarantine lines based on Cunningham’s work. The westernmost dotted red line begins on the northeastern boundary of Clay County. With the exception of southeastern turns in Coleman and Kimble counties, it meanders generally southwest before terminating on the Texas border in Maverick County. A dashed line that Cunningham describes as “perhaps a satisfactory temporary line” starts further east in Montague County on the Red River and cuts straight across the state to end in the same location. Objectors to this line “rather favored” the third line, located further southeast and represented by crosses, that embraces a significantly larger portion of the state as healthy cattle territory. Most cattlemen agreed that a combination of these lines was a reasonable quarantine, south of which environmental factors were more likely to contribute to the fever’s spread. In perhaps a nod to the influence of local politics and economics on the decision-making process, the larger Bureau of Animal Industry report (in which Cunningham’s report appears) notes that “different organizations of stockmen and different individuals have different ideas as to the location of the infected district in the State, and these are usually presented in general terms as conclusions from their experience in the country referred to.”[7]

Southern cattle fever drastically changed government regulation of agricultural health and safety standards in the United States. Nearly 150 years after ranchers recognized its symptoms, southern cattle fever, combined with the rise of fenced-in ranches and the explosive growth of railroads, sounded the death knell for Texas’ struggling cattle-drive industry.

---------------------------------------------------------

[1] Cecil Kirk Hutson, "Texas Fever in Kansas, 1866-1930," Agricultural History 68, no. 1 (1994): 74-75; T. R. Havins, "Texas Fever," The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 52, no. 2 (1948): 149-162.

[2] Hutson, “Texas Fever in Kansas, 1866–190,” 75.

[3] Food Safety and Inspection Service, “Our History,” accessed Sept. 29, 2021, https://www.fsis.usda.gov/about-fsis/history.

[4] “Department of Agriculture. Bureau of Animal Industry. 1884-2/23/1942 Organization Authority Record,” accessed Sept. 29, 2021, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/10481710.

[5] Jimmy M. Skaggs, “Cattle Trailing,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed October 19, 2021, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/cattle-trailing. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

[6] United States Bureau of Animal Industry, Annual Report of the Bureau of Animal Industry for the Year 1885, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1886, 271-72.

[7] Ibid., 271-73.

Photo: Julius Bien & Co. Lith. New York, [1885] Lithograph