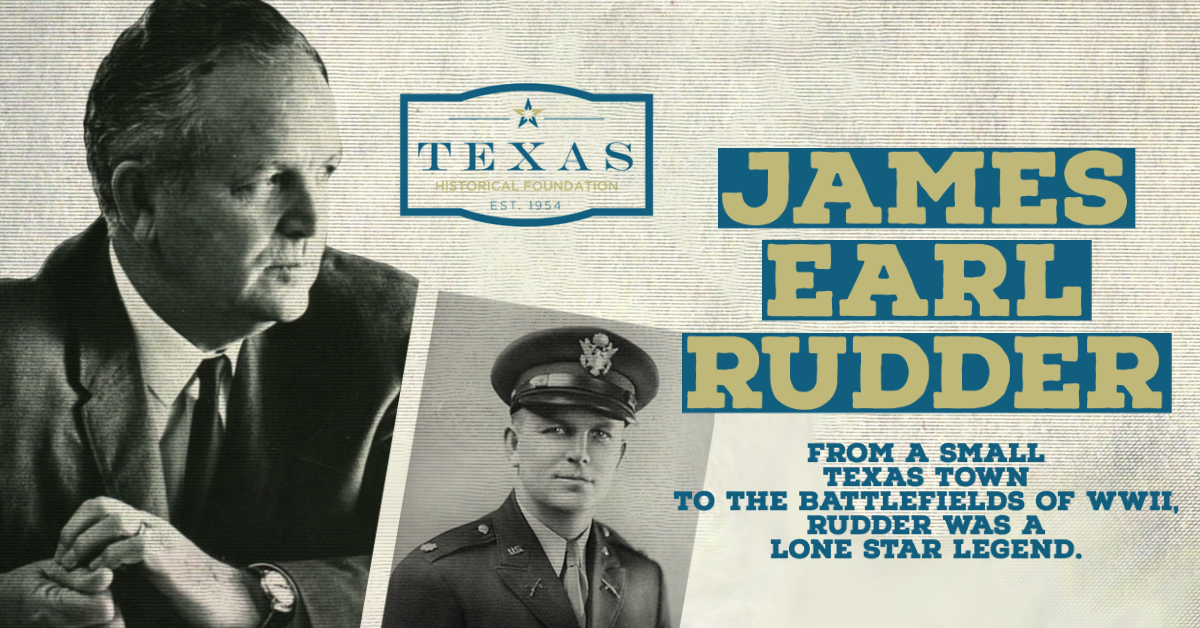

Sometimes, extraordinary times bring forward extraordinary heroes.

Born on May 6, 1910, James Earl Rudder started life in the small town of Eden, 45 miles southeast of San Angelo. After a typical Texas childhood, the 18-year-old attended John Tarleton Agricultural College in Stephenville for two years before transferring to Texas A&M. Rudder graduated in 1932 with a degree in industrial engineering and also received his commission as a second lieutenant in the United States Army Reserve. His first full-time job was teaching at Brady High School where he also coached football and basketball. There, he met Margaret E. Williamson, and the couple married in June 1937. The following year, Rudder accepted an offer from Tarleton Agricultural College to coach the university’s football team and teach. The newlyweds relocated and started a family, welcoming the first of five children in 1940.

On the heels of the United States entrance into World War II in December 1941, Rudder’s military reservist status shifted to active duty. He quickly rose through the ranks. By 1943, he had been promoted to lieutenant colonel and was given an assignment where he put his instructional skills to good use. The young officer had been chosen to lead and train the 2nd Ranger Battalion, a newly formed special forces unit stationed in Tennessee. These soldiers had to be prepared to take on the hardest combat tasks imaginable, including the ability to navigate difficult terrain and operate in enemy territory, sometimes without support or reinforcements.

The battalion’s mission eventually sent them to the coast of Normandy as part of the 1944 D-Day Invasion. There, Rudder and his Rangers were charged with seizing and securing Pointe-du-Hoc, a 100-foot cliff overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. The precipice was crowned by extensive fortifications, including German cannon that could shell the landing beaches below with ease, slaughtering American troops as they came ashore.

Rudder, just 34-years old, and his elite soldiers faced the biggest—and most dangerous— challenge of their lives. The unit would have to make an amphibious assault, coming ashore on to the beach at the base of Pointe-du-Hoc while under heavy German machine-gun and cannon fire. Then, the specialized force would need to successfully climb the treacherous cliff face with ropes and ladders in order to eliminate deadly enemy artillery at the top. One naval planner at the time could not believe the seemingly impossible task that Rudder and his batallion were being asked to accomplish, saying, “It can’t be done. Three old women with brooms could keep the Rangers from climbing those cliffs.” Even so, the lieutenant colonel and his 225 men were ready.

At 4:45 a.m. on June 6, 1944, the Ranger unit left their transport ships in small boats, traveling on rough seas for an hour before spotting the looming cliffs. The order was to start the attack at 6:00 a.m., before sunrise, with the goal being to surprise the enemy. However, many of the boats steered off course in the darkness, delaying the planned pre-dawn arrival. One vessel flipped, tossing nearly two dozen men into the ocean; another took on water and sank. Rudder’s boat was among those that arrived at Pointe-du-Hoc late, just as the sun rose. By that time, the Germans already had spotted the American forces coming ashore and were repositioning their troops on the cliff above to inflict the most damage on the Rangers below. However, the battleship U. S. S. Texas, along with other U. S. warships, began firing their cannon, shelling the ground behind Point-du-Hoc fortifications and keeping the Germans pinned down.

Rudder and his Rangers used rocket-propelled launchers to shoot hooks with attached ropes to the top of the cliff, and carrying ladders borrowed from the London Fire Department, they made the hard climb to the top. Driving off enemy troops, the elite soldiers settled in to defend what they had gained.

For two days, the Germans tried to force the Rangers to retreat, but with no luck. When U. S. Army reinforcements arrived, only 90 of the 225 soldiers from the 2nd Battalion had survived the D-Day attack, and Rudder had been wounded twice.

After his heroic action at Pointe-du-Hoc, Rudder took command of the hard-fighting 109th Infantry Regiment, a part of the 28th Division that saw heavy fighting during the Battle of the Bulge.

By the end of World War II, Rudder was a full colonel, awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the Silver Star, and Oak Leaf Cluster. [He was promoted to brigadier general in the United States Army Reserve in 1954 and then to the rank of major general three years later.] When the Texan returned home in 1945, he became co-owner of a local business and went on to serve as the mayor of Brady from 1946 to 1952. He was also a friend and adviser to Lyndon B. Johnson.

In 1955, Rudder was appointed as the Texas Land Commissioner [after James Bascom Giles was removed from the position under the cloud of scandal] and then was elected to that office the following year. During his three-year tenure, the decorated World War II veteran was instrumental in reorganizing and improving the Texas General Land Office. Rudder left the state agency to serve as the vice president of Texas A&M and then became the university’s 16th president in 1959. He remained in that role until his death on March 23, 1970, just short of his 60th birthday.

From the football fields of Brady, to the cliffs of Pointe du Hoc, to the halls of the state government, to the highest post at Texas A&M, James Earl Rudder lived an amazing Texas life.