Hye, Texas, is not much of a place in terms of being a bustling burg. It has a post office—and a zip code—but never has been an incorporated town, per se. Hiram “Hye” Brown and his folks settled in this little patch of Blanco County in 1872, and opened a store on the Pedernales River along the Fredericksburg to Austin road to provide goods for travelers and the other settlers drifting into the country, competing with merchants in nearby Stonewall, settled just two years before.

There had been folks who had come earlier, like the Germans who founded Fredericksburg up in Gillespie County thirty years before, but that was also twenty miles away to the west. Likewise, there had been ranchers in the region since 1845, but Brown brought the trappings of civilization to that stretch of road and river.

The hill country hamlet took a great leap forward in 1886 when the post office came in, with Brown serving as the first postmaster. Other businesses came to town, too, and by the turn of the century a grist mill and cotton gin got their mail at the store in Hye.

Still, it wasn’t much of a town. When James Polk Johnson kicked off the creation of Johnson City in 1879 just ten miles east and a little north, Hye was destined to live in its shadow, especially when the new town captured the county seat a decade later. Hye would have to be content to be that little store and cluster of enterprises on the way between someplace more important.

Yet, little Hye would become famous for one of the more unusual Texas stories of all time. It was home to the world-famous, all-brother baseball team.

In the 1920s and 30s, baseball was a mania in the Texas Hill Country. “Hill Country baseball was a social event in those days—part athletic contest and part community picnic,” wrote Michael Barr in the Blanco County News. “Every town of any size, and some places that weren’t towns at all, had teams. Big crowds turned out to watch the games. There wasn’t much else to do on Sunday afternoons in the 1930s.”

Times were tough, but baseball didn’t require much of an investment in terms of equipment or training. A kid with instincts armed with a piece of lathed wood could try his luck at swatting the horsehide, which was perhaps the only store-bought item in the game. Any pasture would do for a game, and a feed sack stuffed with switchgrass would serve nicely as a base.

“Baseball was more than entertainment,” Barr continued. “It was a respite from tough times. It helped a generation of isolated Hill Country folk endure the Great Depression. Baseball was the peoples’ game.”

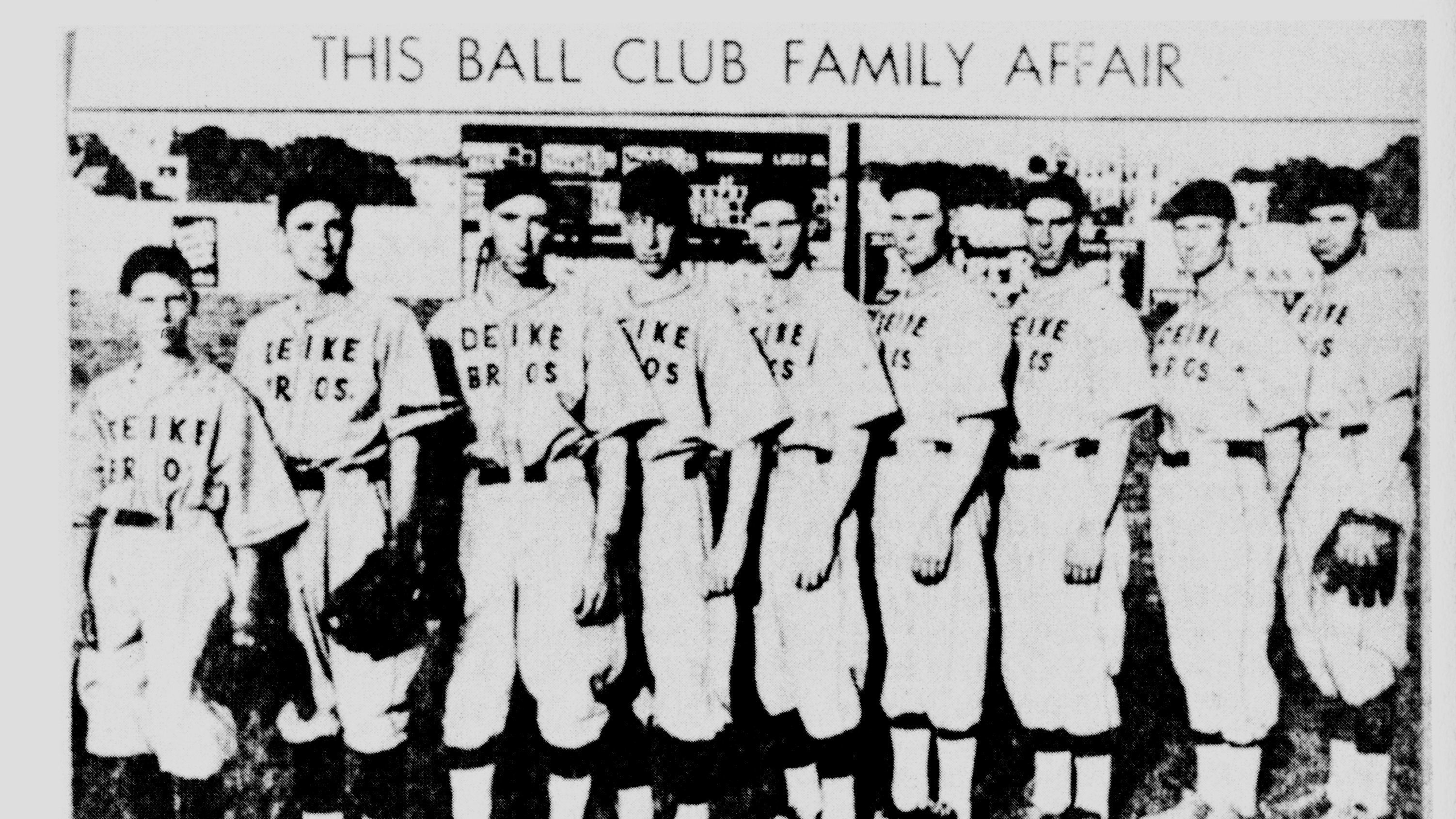

Some of the folks taking refuge in the game were Fritz Deike’s nine boys. Well, most of them at least. Some were too young to keep up, so friends and neighbors filled in. Eventually, though, the Deike brothers, spanning in age from 13 to 32, could field a team of their own—when they weren’t working on the farm, at the store, or in the cotton gin.

Theirs was not a toney team. Up in Fredericksburg, there was a regular baseball field that sat in the middle of the horse track at the old fairgrounds, and another at Seipp’s Park. They had maintained grass and lanes between bases, and even bleachers for onlookers.

Those were fancy city diamonds compared to Hye. The field there was behind the store complete with chicken wire backstop and bases made of burlap sacks full of sand. Dieke family sheep kept the grass short—and fertilized. If you wanted to sit and watch, you needed to bring you own barrel, bale, or blanket.

Each of the boys had their own particular gift. Marvin brought the heat from the pitcher’s bump and had a wicked weapon—the dreaded 12/6 curve that started at noon and dipped to six. Emil played first, while the twins—Clarence and Ernest covered second base and center field. You might get past one of them, but not both. Levi covered shortstop and managed the team while Fred played third. Victor was in left field while Edwin, blind in one eye, was in right.

A kid from a nearby ranch named Lyndon Johnson would fill in at first from time to time until other ambitions took him to bigger arenas. “He was a darned good first baseman,” recalled Fred. “Had a lot of reach. Not many ground balls got by him that I can remember. And he could hit pretty well.”

Deike Baseball Team; Photo by Hill Country Portal

By 1935, the boys mostly just played as a family, occasionally taking on out-of-town rivals but still keeping it fun. That was, until a traveling salesman for the Nueces Coffee Company of Corpus Christi arrived in Hye, peddling at the Deike’s store.

The drummer was fascinated by the story of the all-brother’s baseball team, and before long a letter arrived at the post office offering the Dieke’s an opportunity of a lifetime.

There was another all-brothers baseball team, it turns out. This bunch, the Stanczaks of Waukegan, Illinois, had quite a reputation as a semi-pro club. What if, the letter went, the Dieke’s from Hye, Texas, squared off against these smug Yankees and taught them how ball was played down South. The Nueces Coffee Company would supply uniforms—the boys’ first—and $600 in travel money (that’s more than $11,000 in current dollars) to get them up to neutral ground, Wichita, Kansas.

The Texans took the bait. Promoters scheduled the duel for August 18, 1935, and billed it as the All Brothers Baseball Championship, an exhibition game as part of the National Baseball Conference semi-pro tournament series being played in town. The Dieke brothers loaded into two Model A Fords and spent nearly a week getting up to Kansas where they found themselves in baseball heaven. One notable standout? Leroy “Satchel Paige of the Bismark (North Dakota)” Churchills, who would lead his team to win the whole show after pitching sixty strikeouts across four games.

The Dieke brothers, though, were literally out of their league. The Stanczaks fielded three players with professional experience, and those boys had been playing together longer. Another, at third base, was also a Catholic priest. A brother who was a father, as it turns out.

Other odds continued to stack against the Texans. The game would play at night. The Dieke boys had never played after sunset, and certainly not under lights. The fellows from Illinois had depth. The Texans had pluck. It showed. The men from Hye scored first, logging three runs in the top of the second inning. Then, Marvin’s arm wore out, and his unhittable curve ball quit slinging and whipping right and left as intended. It went flat, and just hung over the plate like a meatball. The Stanczak lumber started heating up. In desperation, Fred moved from third to the pitchers’ mound, but that didn’t help. The Waukegan wonders scored seven by the end of the inning. The Texans would manage another two runs before the game ended, but the Illinois team put up four more to win 11–5.

Defeated but not whipped, the Dieke brothers returned to Hye as heroes. Then, life intervened. Some married and moved away from Blanco County, others simply aged out of the game. Time moved on.

Today, visitors can visit the old store, now a Registered Texas Historic Landmark, and see the team picture of the boys in the only uniforms they ever wore as the all-brothers baseball team from Texas.

USEFUL LINKS:

A book on the subject, published by State House Press

https://www.tamupress.com/book/9781933337135/oh-brother-how-they-played-the-game/

Newspaper Article about it

https://www.hillcountrypassport.com/blanco/article/26403/all-brother-hye-baseball-team

About Hye, Texas

https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hlh61

Place to learn more about this story, and drink wine . . .